Gladiator II is set in a familiar world where politics is a violent game and leaders offer jobs to monkeys

Tim Stanley24 November 2024 The Telegraph

Here’s a true story from a don at Cambridge. He once interviewed a girl for a place to study classics and – this is typical – she had nothing to say. Desperate for an insight into her mind, he asked: “is there anything about the Roman world that interests you?” Pause. “Gladiator,” she said. He thought: I can work with that. “And what interested you about Gladiator?” The politics? the culture? The games? “Russell Crowe,” she replied, and another application bit the dust.

I took mum to see Gladiator II last week at the Imax in London, the screen so big, I almost disappeared up Paul Mescal’s nose. Russell is much missed, but Ridley Scott still has things to say. Critics note that the sequel is more nihilistic than the original, released in the year 2000. The first movie suggested the Rome of Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher-emperor, was a fine idea gone wrong under his son Commodus – and could be redeemed by good men in skirts (Crowe likened his costume to a netball uniform).

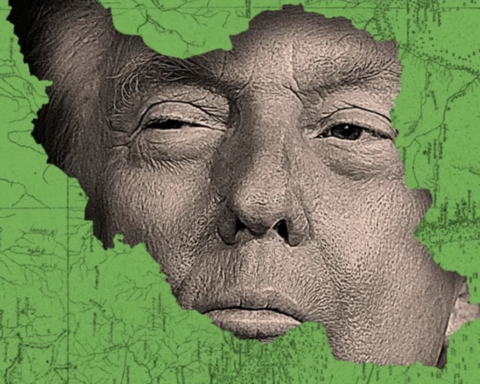

For Rome, read America, pre-9/11 – so full of promise. Two decades later, the tagline of Gladiator II has become “Rome Must Fall”, because it was rotten from conception and gagging for a sacking. The villains are twin emperors who fight endless wars against blended barbarians and distract the deplorable plebs with violent sports. Their faces are painted to disguise syphilis the way Trump’s is to hide old age, and the scene where one appoints his monkey a consul touches a nerve. “Arise Matteus Gaetus…”

But if Gladiator II is a satire on Trump, the pieces don’t fit. Trump is anti-war, not a hawk, and it’s typically conservatives, not liberals, who fret that we’re repeating Rome’s mistakes.

Nationalists point to Rome granting asylum to the Goths, who later sacked it; Christians to its sexual license; rugged individualists, to its loss of martial spirit. “Rome fell,” Elon recently told a podcaster “because the Romans stopped making Romans”: a prosperous society has fewer babies, forcing it to import labour and hire mercenaries. Today’s politicians fiddle with short-term remedies; billionaires like Elon see things in centuries, and societies as systems that break down if they abandon first principles.

Central to this thesis is the idea of cultural suicide. Every society gets wars and plagues, but the hard ones survive while soft ones collapse. Watching these sword and sandal epics, I always worry about the male concubines – there are several camp followers in Gladiator II – for one thinks “when Emperor Kinkii Pervertus is deposed, what are they going to do for work?” Standing about looking effete is hardly a transferable skill.

Well, they could get a job at Jaguar. The car maker’s new ad has been jumped on by Muskites as evidence that our iteration of Rome is on its knees. Eight vestal virgins, covering every ethnicity and body-type bar “Mongolian hunchback”, wander an empty landscape pledging to “delete the ordinary” and “break moulds”.

Jaguar forgot to include a car: a classic example of Westerners handing victory to their competitors by neglecting the basics. But what struck me was the deadness in the models’ eyes. The same deadness one sees in Ukrainian pole-dancers – don’t ask how I know – and in Gladiator’s male concubines, who’ve had the life orgied out of them. Wisdom is understanding that total abandon, like Rome or Hell, is tedious: pleasure as labour, without fruit. The Jag ad ends: “copy nothing”. Yet we’ve seen this novelty a thousand times before, our culture struggles to birth anything new.

Of course, politics is as broken as industry. The US is dominated by a handful of patrician families. Trump, like Julius Caesar, has had to seize power to retain his immunity and stay out of jail. But maybe this is the way of all peoples at all times. Elevating Rome as a historical warning swallows Gladiator’s original theory that it was once stable and noble – yet there wasn’t a century it didn’t experience crisis, and its greatness was built on making life miserable for others. Rome wasn’t demolished in a day; its successors often tried to preserve its better qualities. Likewise, Britain is a kinder, fairer place than it was when we ruled the waves, and some of our unhappiness stems from the lingering belief that we have an ongoing mission to sacrifice ourselves for others. It turns out, for example, that at the same time as the Treasury is taking £500 million from British farmers, it is giving £500 million to farming projects overseas.

Ultimately, Gladiator II offers no answers to the problems it explores. Though it condemns the games, it takes splatty delight in them, showing every injury in gory close-up. The exception is Mescal, who is rammed by a rhino yet walks away with only a small, clean scar on his upper arm. The concubines go: “Ooo!”

He is Captain Kirk; he is Batman. Scott’s Gladiator embodies the Anglo-American, liberal faith in the godlike individual, with scant interest in the fate or agency of the masses. This is a film that barely mentions slavery, Jews or Christians, where the hero has no plan to restore the republic and is only fit to lead because – look away if you don’t wish to know – he turns out to be a royal. As for the monkey: “Coco was one of the better consuls of Rome.” I read that in Edward Gibbon.